AU Professor Kooi’s new book names the 7 best police chiefs

By Hal Conick | December 06, 2021

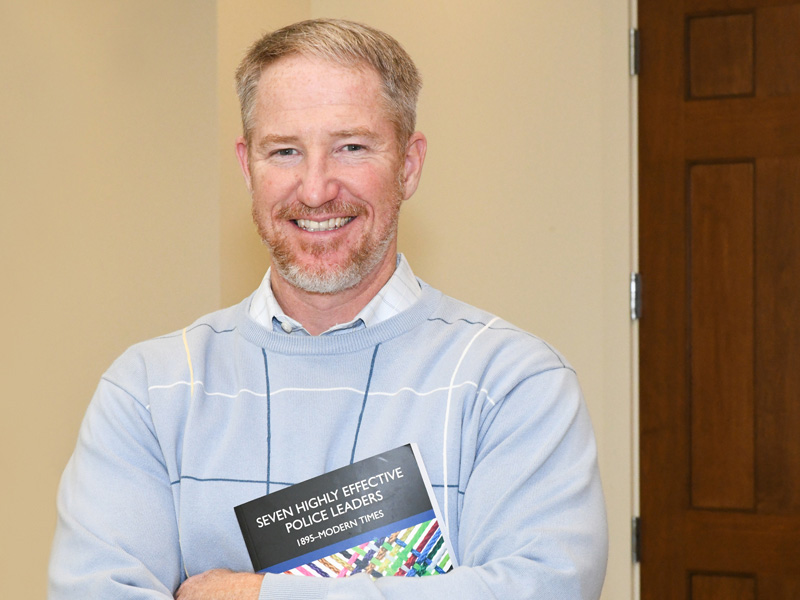

Brandon Kooi, professor of criminal justice at Aurora University, hopes that his new book “Seven Highly Effective Police Leaders: 1895–Modern Times” will provide new insight into what makes a great leader in law enforcement.

Kooi wrote the 448-page book for a wide audience. He wants more people to understand America’s imperfect history of police leadership. The book is designed to educate students, criminal justice professionals, and the general public about a select group of men — and one woman — who were trailblazers in police reform. It is also a book on American history as it relates to race.

“I hope that this book allows us to take a breath of fresh air and realize that race and police reform are topics our country has always struggled with,” said Kooi, who has been teaching at AU since 2007.

AU spoke with Kooi about his book, why he chose these particular seven leaders, and what’s in store for the future of policing. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Aurora University: Were you surprised by any of the themes that emerged as you wrote?

Brandon Kooi: Yes. When leaders govern by fear, it typically leads to chaos. Police leaders who were effective, I found, catered less toward being very disciplinary and restrictive with their patrol officers. Instead, they encouraged creativity and were transparent with the data in a collaborative way.

AU: Who was the most fascinating figure you wrote about?

Kooi: August Vollmer, the first police chief of Berkeley, California, was one of the most interesting. He is considered the father of police professionalism. He was there at the turn of the 20th century advocating for the job of policing to be oriented more to social work while also pushing for officers to earn their college degrees.

He made comments about drug addicts not doing drugs by choice — he said that we need to help offenders. He was also fascinated with how science could advance policing. He was one of the first to bring in fingerprinting and a polygraph — some things later shown to have flaws, but he was constantly experimenting. He only had a seventh-grade education but was a consummate student, reading academic journals, leading the International Association of Chiefs of Police, and attending college courses with his officers. Vollmer instigated the first criminology program at the University of California, Berkeley, and was hired to start a police administration program at the University of Chicago. The Chicago program ended when Vollmer moved back to Berkeley and was never revived.

AU: How did you settle on these seven particular police leaders to profile?

Kooi: I chose each leader in the book to showcase important pieces of American history that tie into modern policing.

For example, not many people know that before he was a U.S. president, Teddy Roosevelt was a New York City police commissioner, fighting police and political corruption.

Then there’s O.W. Wilson, a UC Berkeley student of Vollmer’s who became one of the most important police reform leaders in the country. After he was chief of police in Wichita, Kansas, Wilson became the dean of the UC Berkeley criminology program and then left to serve as the Chicago police superintendent in the 1960s under Mayor Richard J. Daley. He hired a number of civilian academics to assist him in reforming the Chicago Police Department.

One of his primary executive assistants was Herman Goldstein, who would become a personal mentor of mine. Goldstein was an internationally renowned law professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, without a PhD or a law degree, and forged the idea that police leaders should create a culture of problem solvers and analytical thinkers rather than simplistically engaging in exclusive law enforcement.

AU: You profiled the first female police chief. Tell us about the role of women in changing policing.

Kooi: Penny Harrington was the first major-city female police chief in U.S. history. She sued the Portland Police Bureau 42 times, half in federal court, in an effort to allow women to be promoted the same way male officers were, and she suffered a great deal as a consequence of her courageous trailblazing efforts.

I got to personally know Penny as I researched this book. She helped teach some of my classes at AU during the pandemic and even did some mock interview questions with our students. She was very excited to speak with female students who desire careers in policing. She passed away in September, but she had done a lot of work over the past 20 years to really push an increase in women in policing.

The research on what women police leaders do for the subculture and the rank and file is promising. They’re less likely to use force, less likely to receive civilian complaints, and tend to be more emotionally stable than male police officers. That’s one of the untapped areas over the past 20 years — we haven’t seen the diversity within police leadership change very much.

AU: What were some of the reforms these leaders brought to policing?

Kooi: Bill Bratton — who led police departments in Boston, Los Angeles, and New York City — is best known for his use of the broken windows theory of policing, which asserts that any visible signs of crime and disorder create an atmosphere for more serious crime to emerge. He was also known for bringing on board a number of civilian consultants and academics, including Milwaukee native George Kelling, who developed the broken windows hypothesis. Bratton had more success in reforming major police departments than any police leader in U.S. history.

Chicago native Chuck Ramsey was the police chief in Washington, D.C., during the 9/11 attacks, and successfully reformed the Metropolitan Police Department. And Chris Magnus, who made national headlines when as police chief in Richmond, California, he hoisted a “Black Lives Matter” sign at a protest, is rebuilding community trust in law enforcement. He is in the process of being confirmed to lead U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the nation’s largest law enforcement agency.

AU: Why did you write this book now?

Kooi: During the writing of this book, we lost George Kelling in 2019, Herman Goldstein in 2020, and Penny Harrington, in 2021. It’s important for students and the general public to understand how these academics and police leaders made their marks, not by following old traditions, but by critically pushing for change.

AU: What do you hope people learn by reading this book?

Kooi: I hope that it gives the perspective that policing is a noble profession that isn’t as threatened as some believe. I hear a lot of police leaders saying things like, “I would never let my kid go into this profession.” Or “It’s changing too much.” The defunding movement has rattled a lot of people, but we are now seeing more reasonable conversations.

There is an enormous potential to create an authentic paradigm shift and redefine the role that the police serve in society. We can do this in a way that isn’t threatening to the safety of police officers, but instead creates a better environment for them. The evidence on how to more effectively police our country has been around for decades through the lessons of these seven highly effective leaders. Taking the best strategies from each and entering their leadership lessons into the national consciousness would do wonders for the reform movement.

The Top Seven

Teddy Roosevelt – New York

August Vollmer – Berkeley, California

O.W. Wilson – Wichita, Kansas, and Chicago

Penny Harrington – Portland, Oregon

Bill Bratton – Boston, New York, and Los Angeles

Chuck Ramsey – Chicago, Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia

Chris Magnus – Fargo, North Dakota; Richmond, California; and Tucson, Arizona; U.S. Customs and Border Protection nominee